Reconsider the performance benchmarks in Python web development

A few words on common misunderstandings and performance tips of web development benchmarks.

Overview⌗

As of 2020, amongst the various web benchmarks, the most prestigious and reliable one would be TechEmpower benchmarks. Despite the fact that asyncio-based web frameworks prevail on performance in theory and in practice, how performant those frameworks are in pragmatic environments remains to be inspected.

According to TechEmpower benchmarks, it can be noticed that some Python frameworks even outperform Gin, the most famous and widely used Go web framework. In this article, some practical experiments will be carried out over the issue.

Common misunderstandings⌗

Probable misuse of the word performance⌗

The following claims are usually found on most web frameworks:

It features a Martini-like API with much better performance – up to 40 times faster. – Gin, 2020

Fast and unfancy HTTP server framework for Go (Golang). Up to 10x faster than the rest. – Echo, before 2017

High performance, extensible, minimalist Go web framework. – Echo, 2020

Screaming-fast Python 3.5+ HTTP toolkit integrated with pipelining HTTP server based on uvloop and picohttpparser. – Japronto, 2020

Let’s ponder: what do they mean “fast” or “high performance”? Handling one request in very short time? Or handling more requests per second? Unfortunately, I don’t think those developers share one understanding on “performance”, but here let’s clarify:

More requests per second, more performant. A more formal definition would be: more requests/responses per second, or RPS, means higher performance.

asyncio does not improve speed, but it does improve throughput⌗

The assumption that asyncio or coroutines can speed up Python programs is a common fallacy. Asynchrony is guaranteed instead.

The following facts have to be revisited before getting into an example:

Synchrony/asynchrony and blocking/non-blocking are orthogonal concepts.

Blocking IO can still be used in an asynchronous coroutine. A more realistic example should be reading files synchronously from hard disks in asynchronous programs.

Coroutines are special (asynchronous) functions, which can be paused and resumed without losing their current states by some supervisor, or “event loop”. In Python 3.5 and before, coroutines were implemented by generators.

async def test():

print("before 1")

await coro1()

print("after 1")

print("before 2")

await coro2()

print("after 2")

return "result"

The test coroutine runs 10 times, numbered as test_1 … test_10, with the following simplified scenario:

test_1awaits some time-consumingcoro1test_2is called and also awaitscoro1await coro1()intest_1returnstest_1resumes

For more details, keep the official documentation under your pillow.

If test is just invoked once, using asyncio costs more computing resources because of excessive event loops and schedulers under the hood. But thankfully the functions to handle HTTP requests are invoked repeatedly as test. These functions probably spend more time on interacting with a database.

An interface between web servers and frameworks called ASGI adopts this idea:

async def application(scope, receive, send):

event = await receive()

data = await read_data_from_db()

await send({"type": "websocket.send", ...})

The coroutine receive transforms HTTP requests into Python dictionaries such as:

{

"type": "http.request",

"body": b"Hello World",

"more_body": False,

}

Calling the coroutine by await send(...) will send the response to client, as imagined, the coroutine application is called every time when there comes a request from a client.

It’s confident to say web servers handle more requests with asyncio, but it cannot speed up one request - in effect, it gets slightly slower in each request.

Tips on performance and benchmarks⌗

uvloop is dope⌗

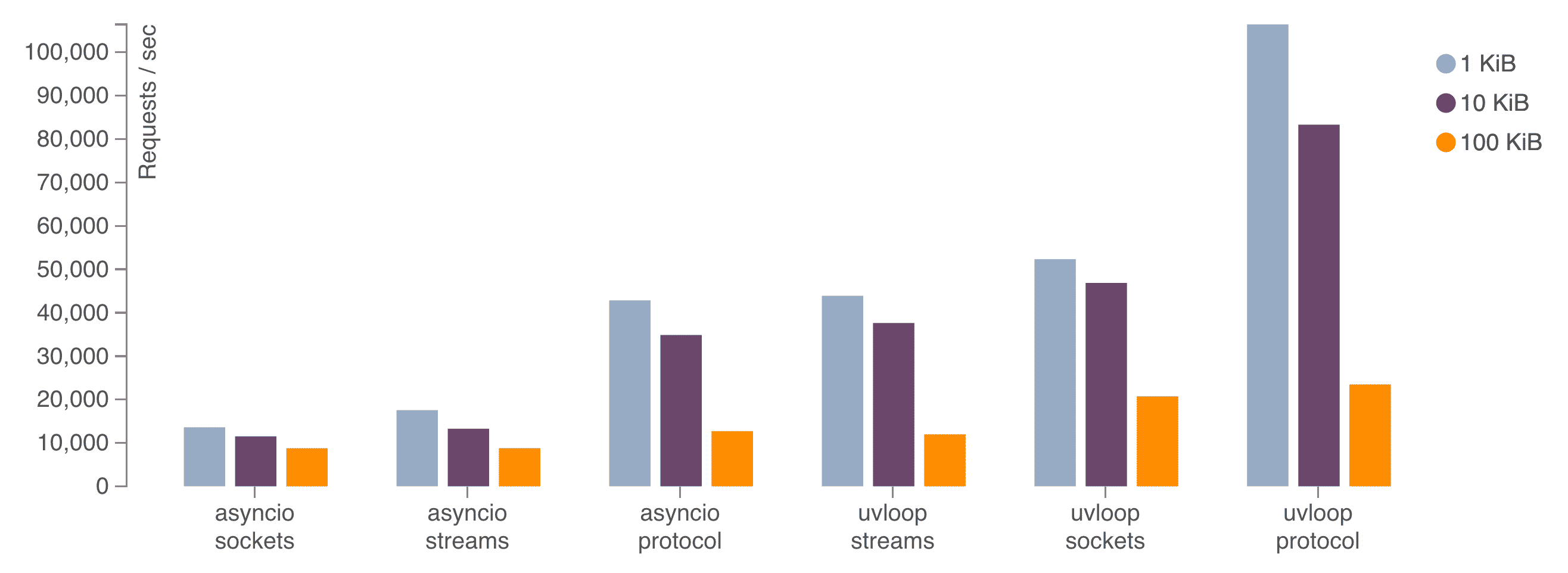

The standard library asyncio helps, but actually it’s just a reference implementation. By leveraging Cython and libuv, MagicStack implemented a faster event loop called uvloop:

Based on uvloop, a fast ASGI server implementation called uvicorn is the de facto server adopted by most asynchronous web frameworks in Python.

More than “Hello world” JSON benchmarks⌗

Most benchmarks are focusing two aspects mainly: JSON serialization and database read/write. JSON serialization is typically a CPU-bound task in contrast database r/w is an IO-bound task. Often this JSON is:

{ "message": "Hello, World!" }

With Bottle/Flask-like styles, routes are defined like:

from awesome_framework import JSONResponse, App

app = App()

@app.get("/")

def handler():

return JSONResponse(dict(message="Hello, world!")) # an explicit JSON serialization pattern

Limited to JSON serialization, Japronto has incredible performance: 133859 RPS on Azure D3v2 instances and this is twice Gin or Beego written in Golang.

A Python novice may be excited, but veterans will inspect again: What is the approximate percentage of JSON serialization in our “yet another awesome web service”? Can it be profiled?

Probably the percentage is pretty low, in fact, the most time-consuming task would be connecting the database, retrieving or updating data and close the connection. And the network-IO eats most of time, no matter how fast JSON serialization is.

No one refuses better performance. To attain extreme JSON serialization speed in Python, check

orjson.

ORM is more practical⌗

In a more practical scenario, it’s necessary to integrate some ORM into the web framework. There are also abundant async or sync ORMs in Python community, such as:

- gino, async

- orm, async

- tortoise-orm, async

- SQLAlchemy, async and sync

- Django ORM, sync

- Pony ORM, sync

Query expressions are similar among ORMs:

class User(Model):

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

name = Column(String)

@classmethod

async def get_user_by_name(cls, name: str):

# in async orm

return await cls.filter.where(name=name)

@classmethod

def get_users(cls):

# in sync orm

return cls.filter.all()

When they get invoked, ORM does the hardest task: converting the query expressions to raw SQLs. As you know, this is pretty sluggish and hurts performance badly, especially in Python.

I didn’t test very rigorously, but it may slow the server by 30% approximately.

If ORM is so slow, what about writing raw SQLs directly?

Raw SQLs outperform ORM, but ORMs are more common⌗

In Python community, most popular database clients are just a thin wrapper over some C implementation, such as psycopg2/psycopg2-binary for PostgreSQL or mysqlclient for MySQL. Prevalent reasons include efficiency, security, code reuse, etc.

However, in asynchronous Python, there is another story. Connecting a database is mainly about setting up a TCP socket, sending some binary data and getting the response, with some additional concurrent connections in a pool. This is akin to what has been discussed above - an HTTP server.

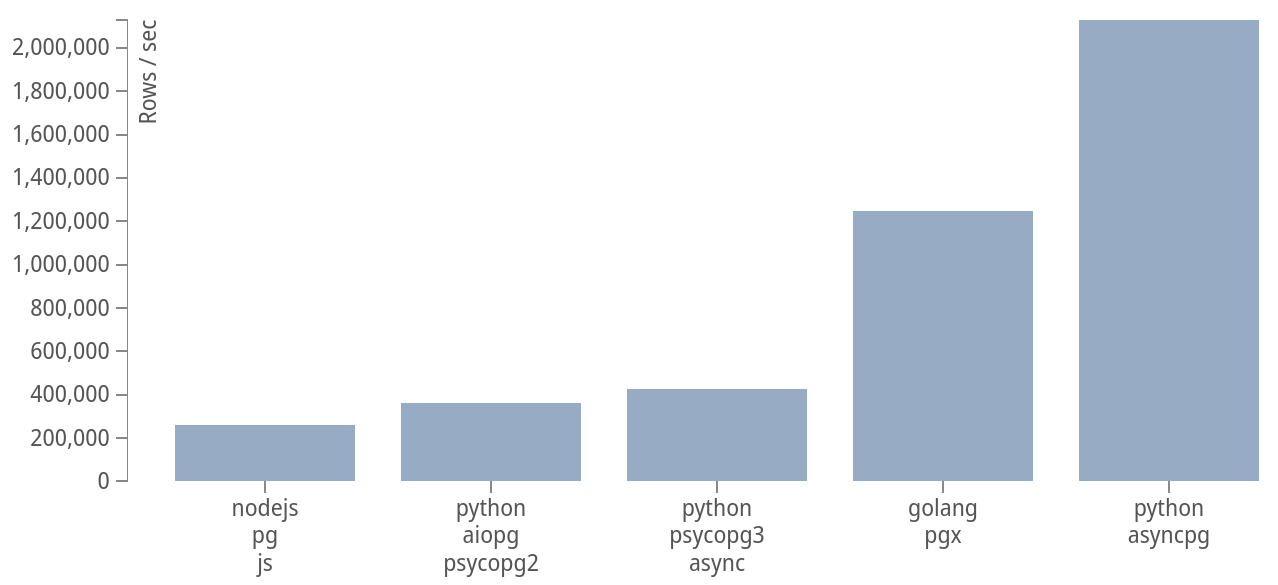

What if uvloop is introduced into database connectors just like ASGI? Well, we are not the first to come up with this notion and there already exists a PostgreSQL connector called asyncpg.

MagicStack is also the author of

asyncpg.

asyncpg has an astonishing performance:

For how did they achieve this:

It soon became evident that by implementing PostgreSQL frontend/backend protocol directly, we can yield significant speed improvements. Our earlier experience with uvloop has shown that Cython can be used to build very efficient libraries. asyncpg is written almost entirely in Cython with careful buffer management and highly optimized data decoding pipeline.

Most benchmarks are combining web frameworks with database connectors and performance are tested by executing raw SQLs instead of ORM queries.

This looks okay, but to what extent are we writing raw SQLs and getting them executed in a connector? At least for me, I only write raw SQLs in ORM only when there are performance problems to resolve, but in most cases, something like cls.filter.where(name=name) is way more familiar.

Everyone blames ORM when they get into performance trouble. Is there any method to get performant as promised in the benchmarks.md?

Baked queries⌗

As mentioned above, converting an ORM query to its corresponding SQL costs considerable time. According to the Pareto principle, we normally spend most of time on a few queries, thus, it’s a natural intuition to cache those queries instead of parsing ORM queries to SQLs over again.

The cached queries are called baked queries.

This technique is different from caching the results from database - you only cache the generated SQLs so there is no need to worry about the consistency.

Below is an example from gino.

Gino is an async ORM based on SQLAlchemy Core and

asyncpgwith rather decent usability and performance.

class User(db.Model):

__tablename__ = "users"

id = db.Column(db.Integer, primary_key=True)

name = db.Column(db.String)

@db.bake

def getter(cls):

return cls.query.where(cls.id == db.bindparam("uid"))

@classmethod

async def get_by_id(cls, uid: int):

return await cls.getter.one_or_none(uid=uid)

With baked queries, you can get around the main bottleneck of parsing ORM queries into SQLs, in most cases this would be a huge performance enhancement:

$ wrk --latency -t20 -c50 -d15s http://0.0.0.0:8080/api/users/1 # pure ORM

Running 15s test @ http://0.0.0.0:8080/api/users/1

20 threads and 50 connections

Thread Stats Avg Stdev Max +/- Stdev

Latency 12.57ms 8.38ms 178.15ms 76.60%

Req/Sec 165.40 79.13 440.00 82.63%

Latency Distribution

50% 12.12ms

75% 16.06ms

90% 19.62ms

99% 39.17ms

49473 requests in 15.06s, 7.03MB read

Requests/sec: 3284.77

Transfer/sec: 477.96KB

$ wrk --latency -t20 -c50 -d15s http://0.0.0.0:8080/api/users/1/bake # with baked queries

Running 15s test @ http://0.0.0.0:8080/api/users/1/bake

20 threads and 50 connections

Thread Stats Avg Stdev Max +/- Stdev

Latency 10.53ms 10.43ms 156.56ms 96.66%

Req/Sec 211.44 69.41 560.00 76.27%

Latency Distribution

50% 9.07ms

75% 11.34ms

90% 14.57ms

99% 61.73ms

63338 requests in 15.06s, 9.00MB read

Requests/sec: 4206.11

Transfer/sec: 612.02KB

$ wrk --latency -t20 -c50 -d15s http://0.0.0.0:8080/api/users/1/raw # raw SQL

Running 15s test @ http://0.0.0.0:8080/api/users/1/raw

20 threads and 50 connections

Thread Stats Avg Stdev Max +/- Stdev

Latency 9.12ms 6.35ms 125.16ms 93.34%

Req/Sec 233.71 69.49 520.00 71.32%

Latency Distribution

50% 7.80ms

75% 10.08ms

90% 13.39ms

99% 38.28ms

69947 requests in 15.05s, 9.94MB read

Requests/sec: 4647.83

Transfer/sec: 676.30KB

Revised benchmarks⌗

Now you probably agree that we should run benchmarks with an ORM. Let’s design some test vectors:

- FastAPI/Sanic + gino, raw SQL

- FastAPI/Sanic + gino, without baked queries

- FastAPI/Sanic + gino, with baked queries

- Gin + raw SQL

I’ll omit the details here lest Go manias be irritated. In conclusion, the performance (RPS) ranking would be:

- Sanic > FastAPI ~= Gin

- Raw SQL > baked queries » ORM

- Gin, Raw SQL ~= FastAPI, baked queries

Sanic performs really well, but if automatic request parameter validation or OpenAPI documentation is necessary, FastAPI would be a better (or perhaps the only) choice.

Conclusion⌗

Asynchronous Python community is growing rapidly and new libraries and frameworks are always emerging. With blazing-fast development efficiency and comparable performance to NodeJS or Golang, asynchronous Python is winning greater popularity in web development steadily.

Trivia⌗

Gin’s annoying 406 errors⌗

If you set wrk -c to 200, there may come many HTTP 406 errors when testing Gin. The simplest solution is to set the concurrency to 50.

Proper pool size setting⌗

DB_POOL_MAX_SIZE should be greater than concurrent wrk connections to avoid frequent database connection acquirements.